Table of Contents

Conspiracy: A Brief Introduction

The Defendants: Who are the 120?

Racketeering Enterprise Affecting Interstate Commerce, or Indigent Defendants?

The Charges: What are the 120 accused of doing?

115 of 120 Disposition Charges: RICO, Narcotics, Possession of Firearm

Predicate Acts For RICO and Drug Conspiracy Charges

Conclusion Relating to Overbreadth of the Bronx 120 Indictments

The Outcomes: What happened to the 120?

Repeat Prosecution for Past Conduct

The Process: What process characterizes mass gang indictments?

Pre-Trial Detention, Bail, and “Release” in Gang Cases

Summary

In recent years, takedowns of gangs and crews in New York City have led to mass prosecutions of multiple defendants for conspiracy and RICO (Racketeering Influenced Corrupt Organization Act) 1 conspiracy charges. While the takedowns are generally accompanied by intensive media coverage, information about the charges, process, and allegations against individuals caught up in these takedowns is not readily accessible.

This report looks into the largest of the mass gang prosecutions, the takedown of the Bronx 120 in April of 2016. This prosecution was brought by the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York when the office was headed by Preet Bharara.

The report seeks to answer two central questions and proposes additional research relating to a third question.

First, were those swept up in the Bronx 120 takedown “the worst of the worst” or was the indictment overbroad?

Second, was the process afforded each defendant charged in the Bronx 120 takedown consistent with the fundamental principles of our criminal justice system?

Third, are there concerns about the use of gang RICO and conspiracy indictments that merit further research?

The conclusions of this report are as follows:

The Bronx 120 mass indictments are clearly overbroad.2

- 35 defendants were convicted of RICO or narcotics conspiracy based on marijuana sales

Short sentences suggest that over a third of defendants were not considered serious offenders

- 22 of the defendants received time served (excluding cooperators)

- 3 defendants received nolle prosequis (declined prosecutions)

- 18 of the defendants were sentenced to terms of less than 2 years

50 - 60 defendants were not alleged to be gang members

80 defendants were not convicted of violence

Only 40 of the defendants appear to have prior felony convictions

Nearly half of the defendants had previously been prosecuted for the same conduct that formed the basis for their inclusion in the mass indictments

Fair process is not afforded in these mass indictments.

Nearly all defendants are held without bail or subjected to house arrest

Indictments do not specify the alleged conduct, so defendants and defense counsel cannot effectively advocate for release or prepare for trial

Individuals are prosecuted a second time for conduct that has been subject to prior adjudication in state courts

Mass indictments fail to safeguard the public’s interest in transparency and speedy trials

The Bronx 120 mass indictments suggest that additional research is needed to answer the following questions:

Why are individuals who are not gang members included in gang prosecutions?

Why are individuals who have not engaged in violence included in gang prosecutions?

What criteria are gang units and prosecutors using to build these cases?

Do these mass indictments produce wrongful convictions by way of either pleas or trials?

What alternatives to building large cases against underprivileged youth of color are available?

Introduction

The Bronx 120 Raid

In the pre-dawn hours of April 27, 2016, nearly 700 officers in riot gear descended upon Eastchester Gardens and the adjoining neighborhood along White Plains Road in the Bronx. The officers were from the NYPD, ATF, DEA, and Homeland Security. Helicopters hovered overhead as armed SWAT teams used battering rams to execute no-knock warrants. They were arresting defendants charged in twin conspiracy indictments. The defendants and the raid have come to be known as the Bronx 120 for the 120 defendants named in the indictments. Preet Bharara, then-United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, announced that the raid was believed to be the “largest gang takedown in New York City history.”3

The Context: Increasing Use of Mass Gang Indictments

While the Bronx 120 was the largest “gang takedown” in New York City history, it was just one of many gang conspiracy cases resulting from collaboration between the NYPD and local and federal prosecutors in New York City. In the past several years, prosecutors in New York City have collaborated with law enforcement to obtain mass gang indictments based on conspiracy charges.4 In particular, the New York County District Attorney’s Office under Cyrus Vance Jr. and the Southern District of New York’s United States Attorney under Preet Bharara and his successors have pursued these indictments.5 Like the federal indictments state “gang takedowns” culminate in pre-dawn raids accompanied by significant media coverage. After the helicopters, SWAT teams, TV cameras, and press disperse, headlines accompanied by photos of black and brown men in handcuffs announce that a local crew or gang is responsible for terrorizing a New York City neighborhood and has been rounded up for prosecution. After the initial spate of news coverage, information about the outcomes or processing of these mass indictments is not easily accessible.

Both the NYPD and prosecutors have characterized gang conspiracy cases as targeting “the worst of the worst.” As the January 2016 Police Commissioner’s Report states:

“We decided to go after the worst of the worst,” Deputy Chief Catalina [commander of the NYPD Gang Division] said. “To use the intelligence we have gathered to figure out who they are and how to target them.”

As gang members and perpetrators have grown younger and younger, fewer of them are involved in drug trafficking, which had been the traditional avenue to arresting violent gang members. Now the gang division builds violence conspiracy cases, finding the evidence from social media, jailhouse calls, confidential informants, and other sources to lay out the pattern of past violent acts and tie the pattern to multiple gang members.

“The violence conspiracy case has been a game changer,” Deputy Chief Catalina said.6

Or as a Chief Assistant District Attorney in the Manhattan DA’s office put it:

“When we first start, a crew might have hundreds of people in it. We then start to narrow, and we focus, like a laser, the worst of the worst,” says Chief Assistant District Attorney Karen Friedman Agnifilo. “We are very careful to make sure that we have evidence that we can prove at trial, that these weren’t just kids who like to hang out with the gang [but] members who are really a part of the violence.”7

The Inquiry

While prosecutors and police claim these raids target violent crew members, an examination of the charges, procedures, and factual basis for these assertions is warranted for several reasons. First, are those swept up in these mass takedowns truly “the worst of the worst” or are the takedowns overbroad? Second, even for those alleged to have engaged in the most serious offenses, is the process afforded each defendant charged by way of mass indictment consistent with the fundamental principles of our criminal justice system? Finally, are there concerns about the use of gang RICO and conspiracy indictments that merit further research?

Methodology And Limitations

To begin to answer some of these questions, this report relies on the available public court records from the mass indictments. The Bronx 120 Raid has been prosecuted by the United States Attorney of the Southern District of New York in federal court. The raid resulted in two mass indictments of 120 defendants – United States v. Burrell8 and United States v. Parrish.9

The publicly available information relating to these indictments include the indictments themselves, docket entries, orders, transcripts, memos, judgments, and other documents relating to these cases.

There are certainly limitations related to this methodology. First, the federal records provide relatively rich but variable level of detail regarding the conduct, background, and criminal history of the defendants. The probation report, which contains full criminal history and criminal conduct information, is a sealed document, but often defense and prosecution sentencing memos provide substantial information regarding alleged conduct. Additionally, federal prosecutors sought and obtained protective orders that prevent defendants and their attorneys from sharing the discovery materials (evidence and witness statements) related to these charges. Finally, the Executive Office of the United States Attorneys issued a “full denial based on exemptions” of Professor Howell’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for the racial breakdown of the Bronx 120 defendants and information about evidence seized in connection with the raids in October 2018.10

Nonetheless, information related to bail conditions, appointment of counsel, pleas, trials, and sentences are available for nearly all federal defendants. The transcripts and submissions relating to these cases provide a rich basis to begin the analysis of these takedowns. As of April 1, 2019, 116 of the original 120 cases had concluded. Analysis of the public records for these completed prosecutions provides a reasonable basis to reach preliminary conclusions to the questions posed by this report.

Conspiracy: A Brief Introduction

In federal and state “mass takedown” indictments, defendants generally face conspiracy charges, whether ordinary or RICO conspiracy. While a full explanation of conspiracy law is well beyond the scope of this report, this overview provides readers with a brief introduction to the aspects of conspiracy doctrine that make it such a powerful tool for the prosecution. Conspiracy has famously been dubbed “the darling of the modern prosecutor’s nursery.”11

As a substantive matter, proof of conspiracy does not require proof that a person committed a particular target crime, was present at the time of the crime, or even knew of the crime. Instead, to prove conspiracy, the prosecution need only prove the existence of an “agreement to commit a target crime,” and that some party to the agreement committed an overt act in furtherance of the agreement.12 The agreement need not be explicit, but can be inferred from conduct or circumstantial evidence.13 Thus, although in theory the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt an “agreement to commit a crime,” they need not prove that crimes were ever discussed, planned, or specifically agreed to, instead, they can point to commission of crimes as proof or agreement.14

For prosecutors the procedural and evidentiary advantages of conspiracy charges are particularly significant with regard to proof of prior crimes. In a typical case where an individual is charged with a crime, the rules of evidence preclude introduction of many prior convictions, crimes, or bad acts, unless they relate to credibility. For example, if a defendant is charged with robbing a person at a particular time and place, proof that he robbed someone else or sold marijuana previously is likely to be excluded as highly prejudicial. The question is whether the prosecution can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that at the specific time, date, and place alleged, the defendant robbed the specific victim. If video, forensics, eyewitness testimony, physical evidence, or confessions related to the specific crime are insufficient to prove the specific charges beyond a reasonable doubt, then the accused should be acquitted. Additionally, proof of the crimes of other individuals would be excluded as irrelevant.

In contrast, if a defendant is accused of a conspiracy to commit robbery, evidence of every robbery any member of the group has ever committed, as well as knowledge that the group committed other crimes, can be admitted at trial to support the inference that joining or associating with the group shows the agreement and the intent to agree to commit robbery. Showing that a defendant was nowhere near the scene of the actual robbery would be no defense. Further, proof that the defendant robbed someone else several years prior would be relevant and admissible to show that the defendant would be willing to join in a conspiracy agreement to commit robbery.

Although conspiracy charges do not require proof that any crime has been committed, prosecutors generally submit evidence of completed crimes for each defendant to prove conspiracy charges. The danger in these mass indictment cases is that procedural and evidentiary rules allow proof of wide-ranging criminal conduct over long periods of time, even when a previous prosecution would normally preclude retrial on the crimes.15 The single defendant is faced with the prospect of defending against allegations relating to all the crimes committed by the defendant himself as well as dozens of co-conspirators over a span of years.

Moreover, because conspiracy or RICO conspiracy charges have elements that are different from the target crime, double jeopardy does not preclude trial for a conspiracy to commit an offense to which an individual has already pleaded guilty (or for that matter been acquitted or granted some form of leniency).16 Many of the defendants in the federal mass gang prosecutions face conspiracy charges relating to conduct for which they have already pleaded guilty and served time, or even for cases that were resolved without criminal convictions.

Finally, because the statute of limitations does not begin to run until a conspiracy ends, conduct that would be well beyond the statute of limitations in a non-conspiracy case can still be admissible as both evidence of the conspiracy and as evidence of substantive offenses in the scope of the conspiracy.17

The evidentiary rules also permit statements of any co-conspirator made in furtherance of the conspiracy to be offered for the truth of the matter asserted, an exception to the usual rules regarding hearsay. In a world of social media posting, Facebook braggadocio, Instagram likes, Snapchat stories, and YouTube videos all provide fodder that allows statements of alleged “co-conspirators” to be used without the benefit of cross-examination. When groups of youths are charged, the volume of social media discovery can easily overwhelm appointed counsel.

As Supreme Court Justice Jackson explained in 1949, the challenges for the individual defendant facing conspiracy charges in a mass indictment are daunting:

When the trial starts, the accused feels the full impact of the conspiracy strategy. Strictly, the prosecution should first establish prima facie the conspiracy and identify the conspirators, after which evidence of acts and declarations of each in the course of its execution are admissible against all. But the order of proof of so sprawling a charge is difficult for a judge to control. As a practical matter, the accused often is confronted with a hodgepodge of acts and statements by others which he may never have authorized or intended or even known about, but which help to persuade the jury of existence of the conspiracy itself. In other words, a conspiracy often is proved by evidence that is admissible only upon assumption that conspiracy existed.

A co-defendant in a conspiracy trial occupies an uneasy seat. There generally will be evidence of wrongdoing by somebody. It is difficult for the individual to make his own case stand on its own merits in the midst of jurors who are ready to believe that birds of a feather are flocked together. If he is silent, he is taken to admit it and if, as often happens, co-defendants can be prodded into accusing or contradicting each other, they convict each other.18

Judge Jackson explains that “the growing habit to indict for conspiracy in lieu of prosecuting for the substantive offense itself, or in addition thereto, suggests that loose practice as to this offense constitutes serious threat to fairness in our administration of justice.”19

Despite warnings relating to the potential for abuse and unfairness of conspiracy charges, their use has been tolerated and continues. Conspiracy charges have been used with increasing frequency in New York in “gang takedowns.”

The Defendants: Who Are The 120?

Turning to the Bronx 120, the first question that we sought to answer was: “Who were the defendants?”

Were they the “worst of the worst”? Were they members of a gang? Were they really masterminds of a criminal enterprise with an effect on interstate commerce? 20 What had they done in the past?

Gang Membership

One of the most startling revelations of the review of the Bronx 120 prosecutions is that half of those swept up in the largest gang raid in the history of New York were not affirmatively alleged to be members of either of the two rival gangs allegedly targeted by the mass indictments. The prosecutor’s sentencing submissions and statements affirmatively state that 34 of those subjected to the raid and arrested as part of the RICO case were not gang members. An additional 17 individuals are characterized as “associates of” or “associated with” the two rival gangs. In a government memo for the trial of C.A., 21 the prosecution makes clear that “associated with” does not mean “gang member.” The prosecution states that C.A. is “associated with” but “not a gang member.” Prosecutors also stated at his trial that he was not a gang member. Like many others, C.A.’s association was allegedly selling marijuana in gang territory with gang members’ permission. Thus, in addition to the 34 who are not members of the gangs, another 16 are “associated with” the gangs but not gang members.

Fewer than half of the individuals taken in the Bronx raids and prosecuted by way of mass indictments are affirmatively characterized as “members” of the two rival gangs that were the target of the takedowns. 4 of these defendants contested the gang membership allegation in their sentencing submissions or other statements to the court. 5 other defendants are alleged to be affiliated with other gangs that are not linked to the indictments.

For 13 of the defendants, there are no allegations one way or the other relating to gang membership and little in terms of a record. Many of these defendants received very short sentences early in the process. This treatment supports the conclusion that they were either non-gang members or gang members who had little to no involvement in violent conduct.

Thus, 51 of the defendants swept up in “the largest gang takedown in New York City history”22 were affirmatively not alleged to be gang members. For another 13 there is no clear allegation relating to gang membership. Their dispositions suggest they were not gang members. Fully half the defendants who were swept up in these raids were not alleged to be members of the gangs.

Racketeering Enterprise Affecting Interstate Commerce, or Indigent Defendants?

RICO, The Racketeering Influenced Corrupt Organization Act,23 was designed as a powerful tool to combat organized crime, particularly when such crime infiltrated the legitimate economy – extracting protection money from local businesses, corrupting unions and controlling jobs, and manipulating markets. Congress armed federal prosecutors with the RICO Act not to fight local street crime, but to root out wealthy, criminal enterprises that could hide criminality in legal enterprises or informal associations, retain the most sophisticated legal teams, and avoid prosecution using ill-gotten wealth.

In contrast to the well-resourced “criminal racketeering enterprise” that was the target of RICO as initially conceived, the 120 defendants named in the April 2016 indictment are nearly all indigent. All but three defendants were initially assigned counsel from the Criminal Justice Act Panel, which provides representation to individuals charged in federal court who cannot afford to pay a lawyer.24 There is no record of any objection to the assignment of counsel to these defendants based on indigence. Eventually, only nine of the defendants were able to hire private counsel.

Of the Bronx 120 defendants, the vast majority grew up in the Bronx and were arrested in the Bronx, either in public housing or in the adjacent neighborhood. The sentencing memos that provide background for each defendant tell stories of deprivation, homelessness, families torn apart by immigration removals, incarceration, unmet health needs, and untreated trauma. They also tell stories of individuals who strive within these constraints to obtain employment and education, and often had employment prior to the April 2016 raid.

The appointment of counsel and the undisputed narratives of deprivation that characterize the defendants in the Bronx 120 demonstrate that RICO was used in this case not to target sophisticated white-collar criminals, corruption, or crime syndicates, but against vulnerable, marginalized, and under-resourced individuals.25

Criminal History

One of the questions that inspired this project was whether these alleged gang members were, indeed, the “worst of the worst.” Bharara alleged that for nearly a decade prior to this mass indictment, rival gangs were wreaking untold havoc in the Bronx. New York City is heavily policed, and the era covered by the indictment included the peak of Stop-and-Frisk (with 685,000 reported stops in 2011).26 “Broken Windows” policing27 was also at its height. What were the records of the Bronx 120 defendants? Did their criminal histories earn them a place among the “worst of the worst”?

The publicly available records provide only a partial answer to this question. The probation department generates a Pre-Sentence Report (PSR) for each defendant and the PSR provides the full criminal history, or lack thereof, for each defendant. However, PSRs are sealed and not available to the public. Sentencing memos from the defense and prosecutors often include the criminal history. Defense memos may argue for a low sentence based on lack of criminal history. Government memos may concede a lack of criminal history, or make arguments based on arrests in the absence of convictions, which seems a tacit acknowledgment of the lack of actual criminal history. Where a criminal history exists, defense memos may provide context for prior convictions. Government memos may describe prior criminal history in connection with sentencing recommendations.

Review of the sentencing memos and other relevant statements relating to criminal history of the defendants provides information for 100 of the Bronx 120 defendants. Of these, only 40 had prior felony convictions. 12 had previous youthful offender adjudications28 (about half involving violence and half non-violence) and 2 were previously adjudicated juvenile offenders.29 18 had misdemeanors only – no felonies. 28 had no record of any criminal convictions whatsoever (coded as “no misdemeanor”).

The 17 cases in which sentencing memos did not clearly state whether or not there was a prior criminal record, defendants fell into two categories. First, there were 8 individuals who received very short or “time served” sentences, or non-prosecution agreements. Short sentences seem to reflect agreement that these eight individuals had no significant criminal history. Second, 8 in this group received quite long sentences or faced mandatory minimums. In these cases, there was little discussion of criminal record because even a lack of criminal history was unlikely to make any difference given the mandatory minimums or serious charges involving murder. The defendants who fell into this category received sentences ranging from 60 to 327 months. Finally, the last of the 17 for which criminal history is unclear has yet to take a plea or submit a sentencing memo.

The cooperating witnesses are not included in the chart above. Based on testimony from the two cases that went to trial, most likely had prior criminal convictions.

One of the most troubling aspects illuminated by the competing submissions on prior criminal history and predicate acts was the use of conduct adjudicated in family courts or by youthful offender treatment. Youthful offender treatment is meant to provide young offenders a second chance. Even when prior misconduct was remote and defendants had seemed to turn their lives around after being provided that second chance in the state courts, their youthful conduct was the basis for new felony convictions and new punishment.

N.B.’s story: A Second Chance Denied

The judge looks down from her bench at the defendant standing before her. She sees trouble: a young man, a teenager who just turned 18, brought in for serious charges – two robberies. She also sees hope. The defense and the prosecution agree that this young man should be given a second chance. She has the discretion to provide Youthful Offender status to the eighteen-year-old, despite the severity of the charge.

This discretion is one thing that makes the judge’s job so important, particularly in New York, where even 16 and 17-year-olds were then treated as adults. This discretion was even more important in the Bronx, where so many defendants, like N.B. standing before her, are born with two strikes against them.

If she gives him a second chance, if he rises to the challenge, together they could turn his life around. He will face consequences for his offenses, but also be rehabilitated and go forth as an adult with no criminal record. She has hope and she acts on it.

N.B. is given the chance to avoid prison by completing a demanding program offered by The Fortune Society, which meets five days a week and involves intensive counseling and education. The program is hard on him, he struggles, he messes up, but he keeps trying.

N.B. is nineteen, and thriving. Proud to have completed the Fortune Society program, he gets a job

at Burger King, and plans on obtaining his GED. Life is full of promise. Then, one day, while he waits outside his childhood friend’s home, an SUV with tinted windows pulls up. His friend steps outside, and N.B. watches as his friend is shot in the head and the SUV tears away. N.B. cradles his friend in his arms as the ambulance arrives. His friend dies moments later.Traumatized by the loss of his friend, and terrified to leave his own home, N.B. loses his job. He cannot focus on getting his GED. He cannot bring himself to go outside. He suffers. Time goes by.

With the help and support of his mother and family, N.B. lands a job at a nursing center in Connecticut and then a job in Yonkers in rehabilitation. He wakes up every morning at five a.m. to travel a circuitous route to avoid neighborhood conflict. He is healing, striving to make a life for himself. He meets a young woman, an aide at a group home for the developmentally disabled. They move in together. They start making plans for a family. N.B. is twenty-two.

On April 27, 2016, agents from the FBI knock on N.B.’s door and put him in handcuffs. His girlfriend thinks she is having a nightmare. N.B. is remanded to jail, charged with 119 others from his Bronx neighborhood. He cannot go home. He sits in jail, for a year and three months.

N.B. has not committed any new crimes; he’s been out of trouble since the January 2011 robbery. The raid, and the federal prosecution of him, is based on conduct from before he turned his life around. There is no way to fight back. There can be no winning at trial, because he already pled guilty when he was eighteen.

He pleads guilty to the RICO charge based on the same two robberies for which the judge gave him a second chance five years before the raid.

On July 11, 2017, a federal judge rejects N.B.’s lawyer’s request for time served and sentences N.B. to 72 months in prison, saying that a gun was displayed in the 2010 robbery when N.B. was 17. N.B. is twenty- three. Years after he is given his second chance with the promise that he would enter adulthood without a criminal record, the federal prosecutor and judge imprison him for six years and give him a felony record for the conduct that was the basis of the Youthful Offender adjudication. The promises made to an eighteen-year-old, who showed that hope could win out, are ignored.

Although we did not have the benefit of probation reports or criminal history rap sheets for each defendant, it appears that about one-third of the defendants had a prior felony record.

Race

Data regarding race of the defendants is not part of the official public record.30 For those who are sentenced to federal custody, Bureau of Prison (BOP) prisoner lookup provides race information. However, the BOP lookup classifies individuals as either Black or White, and classified all those with Latinx surnames as white. In our observations of this case, we did not observe any white defendants.Based on sentencing submissions (which often provided race information), observations, BOP lookup, and Latinx surnames, the below chart provides an initial assessment of race.

Age

The average age of the Bronx 120 defendants at indictment was 25 years old. 31 There were 10 defendants who were over 30 at the time of the indictment. The oldest of these was 55. None of these 10 were affirmatively identified as a member of the rival gangs.110 of the defendants were thirty years of age or younger, with an average age of 23. Because the conspiracy allegedly went back to 2007, these 110 defendants’ average age was only 14 when prosecutors claimed that a RICO conspiracy was formed. This age is one at which individuals cannot vote, sign a contract, marry, or even buy a cigarette, and yet they were charged with conspiracy to engage in racketeering activity. Of course, individuals can join an existing conspiracy years after it begins, but many of the Bronx 120 were quite young even at indictment.

At indictment, the youngest charged defendants were 18 and the oldest was 55 years of age. The chart below shows the age of defendants on the date they were indicted. They were indicted for a conspiracy that dated back nine years.

In the press conference just after nearly 700 officers raided Eastchester Gardens and the adjoining neighborhood along White Plains Road with SWAT teams, tanks and helicopters at dawn, then-U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Preet Bharara, took to the podium to say:

Today we announce what is believed to be the largest gang takedown in New York City history. We have charged 120 defendants in two rival Bronx street gangs with racketeering, narcotics, and firearms offenses. In addition, the charges include allegations of multiple murders, attempted murders, shootings and stabbings, committed in furtherance of federal racketeering conspiracies. 32

The statement is accurate but misleading. One would have to read this statement carefully and together with the indictments themselves to understand its import. The 120 defendants arrested in this gang takedown were not charged with murders, shootings, stabbings, or any violence. Instead, allegations of violence were included in the indictments but no individuals were actually charged with these offenses.33 Allegations of violence were included to paint the 120 defendants with a broad brush, to garner public support, and to make splashy news headlines. They created a juggernaut that resulted in the mass denial of bail described below and compromised basics of due process that safeguard both individual defendant’s and the public’s interest in speedy, fair, and public proceedings. 34

The federal indictments themselves are relatively narrow and concise. The four charges in the twin indictments included RICO conspiracy, 35 two narcotics charges, 36 and a charge of possession or use of a firearm in connection with the RICO or narcotics charge. 37 The firearm charge was broad, stating defendants “knowingly did use and carry firearms, and, in furtherance of such crime, did possess firearms, and did aid and abet the use, carrying, and possession of firearms, including firearms that were discharged on multiple occasions.” 38 None of the charges in the indictments unsealed on April 27, 2016 accused any particular individual of particular acts of violence. Some of the defendants were indicted on all four charges, some on only one. The Initial Charges chart shows the breakdown of initial charges.

115 Of 120 Disposition Charges: RICO, Narcotics, Possession Of Firearm

All but a handful of the cases were resolved based on three of the four initial charges.39 69 of the 120 defendants were convicted of Count 1 – the RICO conspiracy charge. 34 defendants were convicted of Count 2 – Conspiracy to Distribute Narcotics. Only 22 of the 120 were convicted of Count 4 – the firearm charge. The disposition numbers add up to more than 120 because some defendants pleaded to or were convicted of multiple charges.Both the RICO Conspiracy and Conspiracy to Distribute Narcotics charges contain additional complexity. For each RICO conviction there were allegations of “predicate acts,” 40 some violent and some non-violent (including marijuana sale). Conspiracy to Distribute Narcotics included both marijuana sales (typically a misdemeanor under New York law) and other drug sales (most often cocaine in crack form).

Information about the specific conduct or predicate acts that were the basis for each conviction is found in the plea allocution transcripts and often repeated in sentencing memos or at the sentencing hearing.

The predicate acts chart (excluding 3 cooperators) shows that the vast majority of defendants were not convicted based on conduct related to the “multiple murders, attempted murders, shootings and stabbings” alluded to in Bharara’s press release and the indictments.

Instead, nearly one-third of the defendants (35) were convicted based on selling marijuana Most Serious Predicate Act as part of either the RICO conspiracy or the narcotics conspiracy. Another 33 defendants’ most serious charge was drug sale (other than marijuana). Only one-third of the defendants were charged with any type of violence or firearm possession.

Put another way, nearly two-thirds of the Bronx 120 were not convicted of violence or firearm offenses.

The Murders

Although the Bronx 120 indictments did not specifically charge anyone with murder, there were five murders referenced in the indictment that led to the raids and the arrest of the Bronx 120 defendants. The indictment did not state who was responsible for the killings, nor alert the court of those who were not alleged to be involved in the killings.

Six individuals were eventually accused of four of the homicides. Three of these individuals were already under prosecution by state authorities before the Bronx 120 raids. One of them had already served more than 6 years of a 14-year sentence in state prison for the killing of Sadie Mitchell in 2009. Some of the defendants resolved the murder charges by pleading to RICO conspiracy with murder as a predicate act. One went to trial and was indicted in a superseding indictment on a murder charge. One was a cooperator and is excluded from the chart above.

114 individuals were not charged with murder.

Conclusion Relating To Overbreadth Of The Bronx 120 Indictments

While the indictments alleged some violent conduct, charging all 120 defendants in mass indictments does not seem justified. About half of those indicted were not members of either of the crews allegedly targeted. Most did not have significant criminal records. Moreover, over half of the defendants were convicted based upon drug sales (some on behalf of RICO conspiracy and others as part of a conspiracy to distribute narcotics), and only one-third were convicted based on gun or violence-related charges.

The Outcomes: What Happened To The 120?

Sentences

The broad range of sentences in these mass indictments provides strong support for the conclusion that the raids and indictments were overbroad, sweeping in defendants that not even the prosecution believed to be “the worst of the worst.”

22 defendants received sentences of time served (average time served was 5.9 months) and 3 received nolle prosequis (declined prosecutions). Another 18 received a sentence of less than two years. As discussed above, 35 of the defendants were convicted based on their role selling marijuana.

The chart below contains dispositions for 115 defendants, excluding two pending cases and three cooperators.

Felonies Versus Misdemeanors

Despite the relatively low sentences and the accusation of low-level sales levied against many of the defendants, nearly every defendant was required to plead to a felony. Only 3 of the 120 defendants received decisions whereby prosecution was declined. Two were allowed to plead to misdemeanors. The 35 accused of selling marijuana (typically a misdemeanor at state law) were all required to plead to federal felonies. Conspiracy and federal sentencing law allows aggregation of the amount of marijuana that all the defendants sold during the span of the conspiracy (120 defendants over nine years). As a result, most individual defendants had to plead to participating in a conspiracy to sell more than 50 kilos of marijuana.

Repeat Prosecution For Past Conduct

In many of the cases, the conduct alleged as predicate acts for the RICO Conspiracy charge or cited as proof for the conspiracy to distribute narcotics or to possess a gun in furtherance of either of these two charges was conduct that had been subject to previous prosecution or decisions not to prosecute. 41 Where defendants were charged with drug distribution, government sentencing memos cited not only convictions for possession or sale of drugs, but also charges relating to arrests with no convictions, or to low-level non-criminal offenses (“violations”) that resulted in only community service or fines.

Those charged with engaging in predicate acts of violence often faced charges that related to previous pleas (as was the case of N.B. above), arrests without convictions, and arrests with convictions for which time had already been or was being served. Others were removed from state proceedings where they were awaiting trial.

We arrived at this conclusion by comparing the statements in sentencing memos, particularly the statements about prior criminal history and those relating to predicate acts for the particular pleas, and the statements in plea allocutions. Additionally, some defendants asked for and received credit for time served in other cases, indicating that the conduct was the same or related. In other cases, sentencing allocutions clearly referred back to prior convictions.

J.B.’s Story – Double Jeopardy Abused

J.B. was responsible for the death of Sadie Mitchell in 2009. He was 18, and belonged to the local crew, BMB – the Big Money Bosses. He shot a gun to scare off a rival who was chasing him, not at the rival but to scare him. The bullet entered the window of Sadie Mitchell and killed the 92-year-old woman as she watched TV in her living room.

Her death was pointless and senseless, the kind that makes headlines and haunts our dreams.

J.B. was promptly arrested. He was prosecuted and pleaded guilty to manslaughter and criminal possession of a weapon. He was sentenced to 14 years in state prison.

7 years later, J.B. was brought from state prison to federal court as part of the Bronx 120 mass indictment to answer for the very same conduct. When the case was resolved, J.B. was convicted of the RICO Conspiracy charge and sentenced to 12.5 years to run concurrent to the 14 years based primarily on the same conduct – the death of Sadie Mitchell.

Why would the federal prosecutor re-prosecute J.B. for the same conduct? How can this even be legal?

There are high profile cases that illustrate why repeat prosecution for the same conduct in different jurisdictions is allowed despite general rules against “double jeopardy” in our criminal justice system. For example, federal civil rights violations were brought against the police officers acquitted on state charges for the vicious beating of Rodney King. This year, Paul Manafort was indicted on state charges for conduct underlying the federal convictions because he may get a presidential pardon for the federal convictions. The purpose of these prosecutions is not that the defendants should be punished twice, but that they should be punished.

But J.B. had already been punished once. He was serving a 14-year sentence under which the teenager would not be released until he was nearly thirty. And the federal prosecution added not a single year to that sentence.

In many ways J.B. was lucky. Unlike N.B. and many other defendants who were given substantial additional sentences and first felony convictions, he received another felony conviction but no extra prison time.

But why re-prosecute J.B.? The prosecution was not about J.B.. It was about Sadie Mitchell, and bringing her story – the 92-year-old victim killed in her home – back into the narrative to justify the mass raids and prosecutions. Never mind that 114 of the 120 were not alleged to be involved with any killing, and that the vast majority were not even alleged to have discharged a gun.

In total, it appears that the evidence to support the charges against nearly half of the Bronx 120 was based on prior arrests and proceedings in state courts. An individual charged with selling marijuana on behalf of a RICO conspiracy, who had several arrests or convictions for possession or sale of marijuana, would face sentencing memos or trials in which evidence relating to this prior conduct could be used to prove the “predicate acts” in furtherance of the conspiracy.

The extent to which conduct that had not resulted in convictions was used to support the new charges and to argue for harsher sentences was surprising.42 Defense attorneys routinely accept “adjournments in contemplation of dismissal” and pleas to violations for minor misconduct, assuring those arrested that they will not have a criminal record. When helping young people who are on the wrong path, the New York State courts provide second chances in the form of programming and youthful offender treatment which results in a sealed record and is not a criminal conviction.43

A great deal of advocacy on the part of defense counsel, well-considered exercises of discretion by courts or prosecutors, and lack of reliable evidence may all justify non-prosecution or non-criminal charges. Still, the Bronx 120 indictments show us that any contact with the criminal justice system, any charges levied against a defendant, can be later offered in bail appeals or sentencing submissions. These contacts and charges will be used by the prosecution to argue for detention and higher sentences, even in the absence of a criminal conviction.

Defense attorneys, judges, and prosecutors in state courts must re-examine the system of pleas and dismissals in light of these consequences. State legislators may wish to revise sealing provisions in relation to arrests that do not result in prosecution and prosecutions that do not result in criminal convictions.

The Trials

Nearly three years after the Bronx 120 takedown, all but four cases have concluded. Each defendant faced a maximum sentence of either 20 years or life. With the exception of the two declined prosecution cases, all but two defendants pleaded guilty.

There were only two trials. These defendants, C.A. and D.T., occupied opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of the severity of the conduct attributed to them. C.A. was not a gang member and was accused of selling marijuana with permission of the gang and to benefit them and with possessing a firearm in connection with marijuana sales. D.T. was accused of being a member of BMB, aiding and abetting murder, and committing other acts of violence.

The prosecution conceded that C.A. was not a gang member. Instead, they claimed that C.A. sold marijuana to BMB, on BMB territory, with BMB permission and at a discount to benefit BMB. C.A. said he sold marijuana for himself. Additionally, the prosecution alleged that C.A. possessed a gun in connection with the narcotic sales or RICO conspiracy. There was no DNA or fingerprint evidence linking the gun to C.A., but he had previously pleaded to an “attempted possession charge” in state court. A police officer was the only witness to say C.A. possessed the gun. C.A. said it belonged to the other occupant of the car.

This officer had a substantiated Internal Affairs Bureau complaint, a substantiated Civilian Complaint Review Board complaint, and six civil suits for charges such as wrongful arrest, malicious prosecution, and excessive use of force that the city had settled. The jury for C.A.’s trial convicted C.A. of all charges. They never knew of the police officer’s record. The government sought and the court granted an order barring defense questioning on the substantiated complaints and the settled civil cases. The only evidence that linked C.A. to the gang was the testimony of a cooperating witness, an old photo with a friend, and a Facebook chat (that C.A. was not involved in) that could be interpreted as the cooperator and another person chatting about getting marijuana from C.A..

D.T. was on the opposite end of the spectrum. In addition to robbery and firearm discharge, D.T. was charged as an accomplice to murder for allegedly handing M.M. a gun with which M.M. shot Keshon Potterfield. There was no doubt from his YouTube rap videos that he was a member of BMB and no doubt that he’d been in trouble before. However, once again, much of the evidence related to the murder hung on the testimony of cooperators (in this case 4 cooperators). The lyrics of his rap songs were interpreted as confessions. The NYPD officer who claimed to have recovered a gun from D.T. also had a record of settled civil suits of which the jury was unaware. He used the twitter handle “@obamahater55,” through which he shared racist content.

Each defendant went to trial alone, but the jury was regaled with descriptions of the violent gangs that they associated with. In each case, the lynchpin witnesses were cooperators buttressed by police officers with records of misconduct that were hidden from the jury. Each was convicted of all the serious charges against them. C.A. received a mandatory minimum for the gun he denied possessing. D.T. received a life sentence plus 55 years, while the actual shooter was sentenced to 327 months (27.25 years) on a plea to the RICO charge with murder as a predicate act.

The Process: What Process Characterizes Mass Gang Indictments?

The “mass gang takedown” indictment shifts the administration of criminal justice in a way that is both unnecessary and dangerous. This section briefly raises four troublesome aspects of the process related to gang prosecutions. The lack of defense counsel objections to these aspects of the prosecutions suggests that they may reflect accepted practices in the federal court system but also suggests that these topics should be added to the list of areas for criminal justice reform.

The Raids

When the indictments of the Bronx 120 were unsealed, 700 officers from the NYPD, ATF, DEA, and Homeland Security all gathered to execute a pre-dawn raid in the Bronx Eastchester Garden and the adjoining neighborhood. With no-knock warrants in hand and helicopters above, fully armed SWAT teams dressed in raid gear used battering rams to break down doors, ordered family members to the floor at gunpoint, and dragged out their quarry.

As discussed above, two-thirds of the targets were not charged with violence. Many of those charged with the worst conduct weren’t even there – they were already incarcerated and awaiting trial or serving sentences. The prosecution had been building these cases for months and the Gang Units had been following these individuals for two years. They knew where they went and where they lived. They could have just as easily waited outside, picked people up at work, at school, or in the neighborhood.

A recent two-part series in the New York Times reports that 81 civilians and 13 law enforcement officers died in SWAT operations between 2010 and 2016.44 The city of Houston has decided to stop using “No- Knock” warrants altogether due to the outsized risks.45 In the case of the Bronx 120 raids, a man plunged to his death in the Bronx on April 27, 2016 when he climbed out the window to evade police. 46

Risk of death is not the only unnecessary harm related to militarized raids inflict. Each defendant was part of a family and part of a community. The fear and trauma inflicted on family members and communities by a military-style pre-dawn raid is not justified by the charges.

Pre-Trial Detention, Bail, And “Release” In Gang Cases

The Eighth Amendment prohibits excessive bail, yet the Bail Reform Act of 1984 allows pre-trial detention “when the accused posed a danger to the public or particular members of the public” 47 or a particular risk of flight. 48 The Bail Reform Act of 1984 creates a statutory “rebuttable presumption” of flight or dangerousness and allows pretrial detention without bail when charges include narcotic offenses carrying potential sentences of ten years or more, or a firearms charge under 18 U.S.C. 924(c). 49 Where the predicate act for a RICO charge is murder pretrial detention without bail is also permitted.50 All four of the charges in the twin mass indictments carry a “presumption” in favor of pre-trial detention.

Pre-trial detention under these provisions is the equivalent of “remand” in New York State court. No amount of money can gain the defendant’s release.

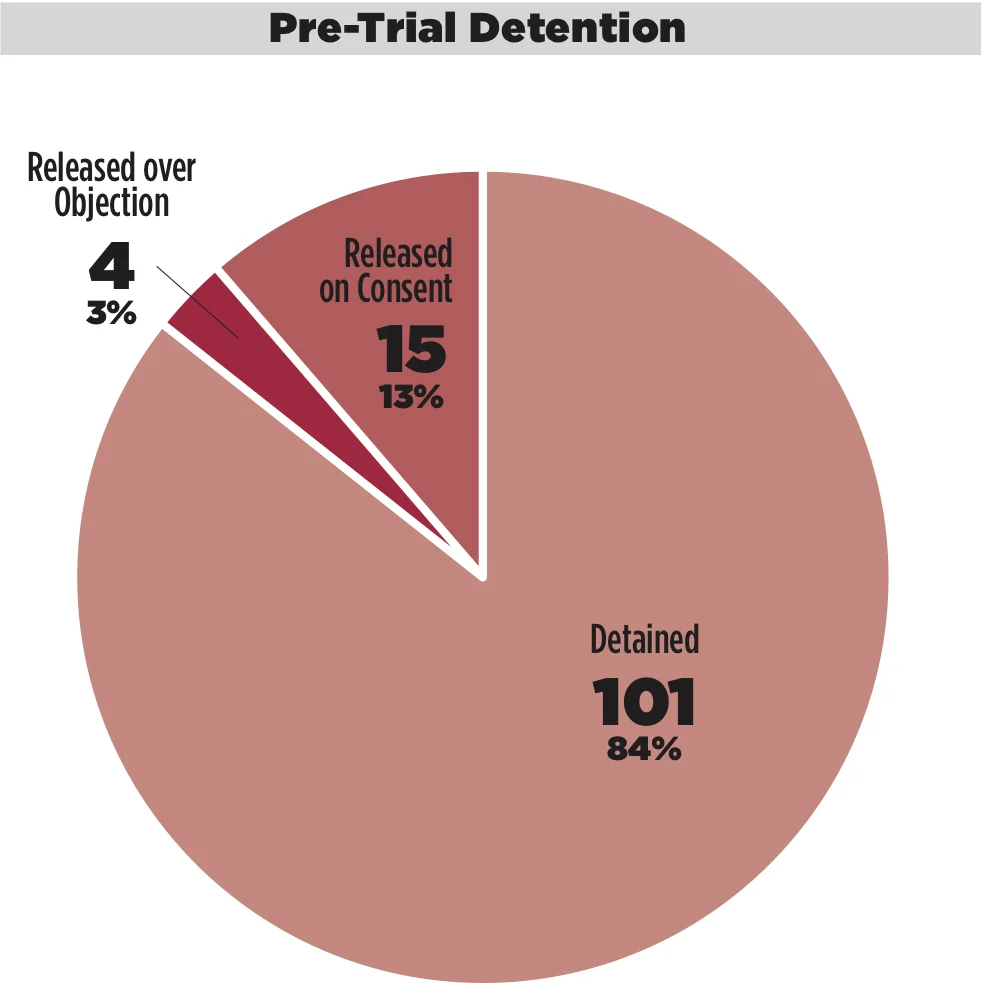

The mass gang indictment takes full advantage of the Bail Reform Act. Without the consent of the government, it was nearly impossible to obtain pre-trial release. Of the 120 defendants, 101 were remanded without the possibility of bail until their cases were resolved. Of the 19 who were released, only 4 were released over the government’s opposition.

The majority of the defendants did not attempt to challenge the pretrial detention determination. Of the 31 who challenged their pre-trial detention without consent of the government, only 4 were successful. 6 obtained favorable initial rulings permitting their release which were appealed by the government and overturned. 20 of those detained without bail had no prior felony convictions. 19 of those who challenged detention and were denied bail were eventually convicted only for narcotics distribution, either marijuana (9) or other narcotics (10).

K.L.’s Detention Saga

K.L. was beating all the odds. He had studied hard through college, as a collegiate scholar-athlete, playing basketball, running track and making the Dean’s List. In 2013, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice. He decided to enroll in an MBA program, and was excelling at it, all while paying it back

to his community in Bridgeport, Connecticut, organizing fundraising events for breast cancer awareness. He coached a kids’ basketball team and created and organized a “Stop the Violence” basketball tournament aimed at raising awareness of gun violence in inner city communities. He became assistant coach of the university’s basketball team, and served as chairman of the university chapter of UNICEF, organizing events on their behalf. And through it all, he was raising a young son, who he proudly took to meet his fellow students and teammates.In his final semester of grad school, on track to receive his MBA, K.L. was arrested. The government argued that he should be detained without bail, even though he had no criminal record, and had never been in trouble.

The Magistrate Judge agreed he should be released at his initial appearance. But the government appealed and the graduate student with no criminal record was detained “as a danger to society.” So K.L. sat in jail.

The semester went on, and ended without him. His classmates graduated, and walked the stage to receive their diplomas. K.L. sat in jail.

The kids he coached played their final games, went away to school, moved on with their lives. K.L. sat in jail.

His 6-year-old son went to school without his dad to walk him there. He celebrated birthdays and milestones. He didn’t understand why his dad was gone. K.L. sat in jail.

K.L. is out now. He was given a sentence of time served. But his life is not the same. He remembers seeing a friend stabbed in the neck while he was in jail. He remembers missing his son’s birthdays. He remembers how full of potential his life was, before the arrest. Even though he completed his MBA program through another school while in jail, his future is not the same. Not with a felony conviction.

The Bronx 120 defendants who were “released” were released under stringent conditions including house arrest, electronic monitoring, and strict supervisions. Not a single defendant was released on recognizance; that is, with no conditions other than to return to court for court appearances and abide by the law. These conditions meant 15 of the 19 individuals who were released were not at liberty to go to school to watch their children’s sports team, sit in the park on a sunny afternoon, or visit a friend or neighbor. Even defendants who were released were generally incarcerated for some time before release. Only two defendants were able to meet the conditions imposed for release on the first day. Others were detained for a week to four months before achieving release. These detentions and conditions result in the loss of employment and other hardships.

The “Lucky” Ones

L.W. was one of the lucky few. Not only was he released, but he was released over the government’s opposition. The magistrate judge who heard his bail application learned that he worked two jobs and had no criminal record. The conditions of release, however, included home confinement. L.W. was detained for 21 days before he could meet the conditions of his release. During his home confinement, L.W. lost both jobs. Eight months later, when he was finally relieved of home confinement, L.W.’s former employer would not take him back because of the pending case. At the end of the case, he was sentenced to time served, and like all but 4 of the defendants, emerged with a felony record. Like many other defendants, the conduct alleged was marijuana sale.

A.M. was even luckier. The government agreed that he should be released. He was not even subjected to house arrest. It took him less than two weeks to meet the bail conditions. In the meantime, he lost his job at the rehabilitation center that gave him the flexibility to both serve as his son’s primary caretaker (his wife was a live-in nursing aide) and to support the family. On May 5, the day before his release, his mother passed away.

Although pre-trial detention and excessive bail is a problem in nearly every court, state or federal, in the United States, the federal courts have services that have rendered bail unusual and unnecessary in many low-level and non-violent cases. The mass gang prosecution of the Bronx 120 defendants allowed Bharara’s office to advocate for pre-trial detention and intensive supervision for even low-level and non-violent defendants. The prosecutor used a narrative of violence and an extraordinarily general indictment to play on judicial fears. As a result, the prosecutor obtained nearly complete control over all 120 defendants from the day the indictment was unsealed.

Indictment Specifity

As mentioned above, the indictments in the Bronx 120 mass gang prosecutions provide no individualized specifics relating to time, dates, or alleged conduct. At early court appearances, the prosecution was given nearly six months to provide defendants with an “enterprise letter,” providing specific allegations as to each defendant’s conduct. Meanwhile the defendants, many of whom had been arrested in the raid, and most of whom were incarcerated without the possibility of release, faced serious felonies carrying maximum sentences of 20 years for some and life for others. Indictments that do not provide information make it impossible to prepare a defense. Additionally, lack of information means that those who are not alleged to be gang members or to have engaged in violence cannot effectively advocate for pre-trial release or even dismissal of charges based on lack of probable cause.

Social Media

Like the broad allegations in the generalized indictments, the prosecution presented social media evidence collected from a handful of the Bronx 120 defendants’ Facebook and YouTube accounts at the start of nearly every sentencing memo, even when the accounts referenced had nothing to do with the particular defendant being sentenced. For each defendant, prosecutors submitted verbatim the same summary of social media activity of several defendants who posted about gang rivalries and norms against cooperating with law enforcement. YouTube music videos made by a few defendants rapping about drug sales, gun possession and/or gang affiliation were also presented in sentencing submissions for every defendant charged, as evidence of their affiliation with criminal activity. Similarly, government letters arguing for detention for those requesting bail mentioned social media evidence from other defendants in the Bronx 120 to show their affiliation with gang violence.

Overall, YouTube rap videos featured only 14 individuals out of the 120. But these videos were presented as not only further evidence of these individuals’ culpability, but also evidence that the Bronx 120 composed a violent enterprise. Facebook posts, photos and messages were also presented as evidence of gang affiliation for 30 people. In some of these cases, a photo of a defendant with friends who were alleged to be gang members, or a post about an alleged gang member was used to show proof of gang allegiance. And for 14 defendants, social media evidence in general was mentioned, though not specified, either during plea or sentence hearings or in court documents.

Although the memos submitted by the government generally referenced the same few posts, the government executed over 100 search warrants on Facebook and Instagram relating to the case. At initial conferences they indicated that for each Facebook return “paperwork can range into the tens of thousands, or even in a couple of instances, hundreds of thousand of pages per account.”51

The use of social media to prove affiliation, association, enterprise and guilt creates dual problems for fair process in the criminal justice system. First, so much of what is posted on social media lacks indicia of reliability – people boast, brag, like, and repost to conform to social pressure. What may be meant as a joke or recognized as a lyric to a favorite rap song is instead interpreted by outsiders as inculpatory. Photos with peers and music videos recorded as artistic endeavors were used as proof of particular crimes and of association in furtherance of a criminal enterprise. Second, the volume of postings put individual defense counsel and defendants at an enormous disadvantage. Detained defendants could not access the information easily to interpret it for their lawyers.

Speedy Trial Waivers, Discovery And Protective Orders

In order to manage these massive indictments, the prosecution requested and the judges granted repeated exclusions of time for speedy trial purposes. An initial five month exclusion through October of 201652 was followed by an exclusion of speedy trial time through November 6, 2017 (18 months after the case was filed) because “this case is so unusual and complex due to the number of defendants, the nature and scope of the prosecution, and the volume of discovery, that it would be unreasonable to expect adequate preparation for trial within the limits of the Speedy Trial Act.”53

These decisions reflect the court’s determination that “the ends of justice outweigh the interest of the public and the defendant in a speedy trial.”54

It is true that no defendant objected to the waiver of speedy trial requirements, but it is important to consider these waivers in context when one considers voluntariness. Each defendant is facing either a maximum sentence of 20 years or life, and each lawyer has little idea what the evidence is against their client. They are at the mercy of the government and rocking the boat by objecting to waivers of speedy trial time could hurt their clients. Without discovery and a sense of how strong or weak the cases are, it would be the foolhardy attorney who stands alone to insist on speedy process in a case involving 60 defendants.

Moreover, no discovery is available at arrest. When initial discovery does become available it includes tens of thousands of social media posts which risk overwhelming defense attorneys.

Additional and critical discovery (the prior statements and reports of witnesses who will testify against a defendant) is available in the federal system only pursuant to 18 U.S.C. §3500, the Jencks Act, and not until the eve of trial. In the two cases where trials were held, and this material produced, it was produced only subject to protective orders that prohibited sharing discovery and required its return and destruction after trial.

It is not only the defendants who have an interest in specificity in charging documents, speedy disposition of criminal cases, and transparency relating to process and evidence. Where the government bundles together dozens of defendants (and even when it does not), the public has its own interest in the orderly administration of justice.

The interest of both the defendants and the public is implicated where pre-trial detention, lack of discovery, and waiver of speedy trial creates pressure to plead to get out of jail. Though many of these sentences are relatively short, each one represents a huge investment in incarceration, and each comes with another investment in post-release supervision. The costs in lost earnings, lost parenting time, and lost education during incarceration for dozens of individuals not implicated in violence are immeasurable, as is the impact on the communities from which they come. These defendants are members of the public, and their families and communities are members of the public, the state and the country. Imposing felony convictions and imprisonment based on mass indictments means that the individuals, their families, their communities, this state, and the country will be paying for these prosecutions long into the future.

Conclusion

The Bronx 120 mass indictments are overbroad.

- 35 defendants were convicted of RICO or narcotics conspiracy based on marijuana sales

- Short sentences suggest that over a third of defendants were not considered serious offenders

- 22 of the defendants received time served (excluding cooperators)

- 3 defendants received nolle prosequis (declined prosecutions)

- 18 of the defendants were sentenced to terms of less than 2 years

- 50 to 60 defendants were not alleged to be gang members

- 80 defendants were not convicted of violence

- Only 40 of the defendants appear to have prior felony convictions

- Nearly half of the defendants had previously been prosecuted for the same conduct that formed the basis for their inclusion in the mass indictments

Fair process is not afforded in these mass indictments.

- Nearly all defendants are held without bail or subjected to house arrest

- Indictments do not specify the alleged conduct, so defendants and defense counsel cannot effectively advocate for release or prepare for trial

- Individuals are prosecuted a second time for conduct that has been subject to prior adjudication in state courts

- Mass indictments fail to safeguard the public’s interest in transparency and speedy trials

The backgrounds of the defendants provide stories of deprivation, untreated trauma and mental health issues, and abandonment. What is remarkable, as one reads through the many depressing sentencing memos, is that so many of these 120 were not in more trouble. So many had no criminal records. So many were not charged with violence in connection with these gangs. So many had dreams and were pursuing them. They made music, the lyrics of which were used against them in bail applications, sentencing submissions, and trials. They moved from the streets of their youth to distance themselves from the violence, seek employment, and build families. There are 120 individual stories that may never see the light of day, and 120 lives forever changed. Some of these defendants appear to have committed serious offenses but many others did not.

In conclusion, the Bronx 120 indictments appear not only to be overbroad and unfair, but they seem profoundly unwise. Prosecutors can use mass conspiracy indictments to round up local crews and gangs and to erase the difference between bad actors and their friends and peers. But they should not. Even the privileged among us would not choose to be held criminally responsible for the conduct of fraternity brothers, high school friends, or even drama club or math team members. Bad decisions and conforming behavior are the norm for adolescents and young adults, but many avoid engaging in violent conduct and others can be helped to develop non-violent responses. Conspiracy is a powerful tool but should not be leveled against the least powerful among us; instead, our goal should be constructive interventions and individualized justice with full due process of law.

Recommendations

The overbroad of the indictments, denial of pre-trial release, lack of discovery, speedy trial waivers, and high sentence exposure leads to very real concerns about the fairness and accuracy of the convictions. The fact that many swept up in the raids and prosecution were neither gang members, nor charged with violence, raises questions about the criteria that gang units and prosecutors were using to levy accusations against individuals. Across the country, gang units have been responsible for some of the largest scandals in policing history, including the Rampart scandals in Los Angeles.55 In New York City, gang unit officers have more misconduct complaints (and settlements) than patrol officers.56

Given these concerns, steps should be taken to avoid similar prosecutions and to investigate other gang takedowns.

General recommendations relating to mass indictments in gang cases:

- Discontinue the use of RICO for loosely organized crews and gangs, since the purpose of RICO is to address sophisticated organized crime;

- Discontinue the use of state conspiracy charges against crews because they arise from the same over-inclusive collaborations as the Bronx 120 indictment;

- Strike mass indictments that fail to specify individual conduct as inconsistent with due process;

- Grant release on recognizance or reasonable bail to defendants in mass gang indictments absent risk of flight;

- Do not re-prosecute for conduct or predicate acts that have already been adjudicated in state court;

- Amend RICO to require a jurisdictional minimum for the impact on interstate commerce of an amount greater than $10 million a year to prevent RICO from being used to bring ordinary street crimes into federal court;

- Provide Cure Violence resources, jobs, social services, and support to communities and individuals at risk rather than conducting year-long surveillance and bringing mass takedowns .

Specific recommendations for convictions based on gang takedowns

- Create a conviction integrity unit to review these convictions;

- Consider reparations for family members harmed and traumatized by the raids;

- Investigate the gang units that helped prosecutors frame these mass indictments to find out how and why non-gang members and non-violent individuals with minimal roles were implicated in these alleged conspiracies.

The Bronx 120 mass indictments suggest that additional research is needed to answer the following questions:

- Why are individuals who are not gang members included in gang prosecutions?

- Why are individuals who have not engaged in violence included in gang prosecutions?

- What criteria are gang units and prosecutors using to build these cases?

- What are the risks of close collaboration between gang units and prosecutors?

- Do these mass indictments produce wrongful convictions by way of either pleas or trials?

- What alternatives to building large cases against underprivileged youth of color are available?

Endnotes

1 The Racketeering Influenced Corrupt Organization Act, 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961—1968. For a useful very brief summary of the RICO Act, see RICO: An Abridged Sketch, Congressional Research Service Report, May 18, 2016; available at https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20160518_RS20376_1e908ea0a5addd8fb01c9942bf17282262e40f72.pdf.

2 I use “overbroad” here in the ordinary non-legal sense, to mean too widely applied, not in the constitutional sense of an overbroad statute that infringes on First Amendment conduct, although the use of association and expression to establish these cases may have a chilling effect on First Amendment conduct as well.

3 Preet Bharara Press Conference USAOSDNY, 120 Members Of Street Gangs In The Bronx Charged In Manhattan Federal Court, YOUTUBE (Apr. 27, 2016), https://perma.cc/7LNR-9PJC.

4 There were 40 “takedowns” in 2016, and 41 as of July 28, 2017. David Goodman, Trump Takes Aim at ‘Pathetic Mayor.’ De Blasio Thinks He Knows Who He Means, New York Times, July 28, 2017. See also, NYPD Gangs & Crews of New York PowerPoint p. 45 (41 case takedowns in 2017 and 498 arrests) available at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4499937-NYPD-Gang-Presentations.html#document/p1.

5 The head prosecutors are identified because mass indictments reflect decisions made at the highest level of the prosecutors’ office.

6 THE POLICE COMMISSIONER’S REPORT JANUARY 2016, at 44, available at https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nypd/downloads/pdf/publications/pc-report-2016.pdf.

7 Ben Popper, How the NYPD is using social media to put Harlem teens behind bars: The untold story of Jelani Henry, who says Facebook likes landed him in Rikers, The Verge (Dec. 10, 2014.) available at https://www.theverge.com/2014/12/10/7341077/nypd-harlem-crews-social-media-rikers-prison.

8 United States v. Burrell, S2 15 Cr. 95 (AJN).

9 United States v. Parrish, S1 16 Cr. 212 (LAK).

10 FOIA request dated 10/2/18, tracking number EOUSA-2019-000093. “Full Denial Based on Exemptions.”

11 Harrison v. United States, 7 F.2d 259, 263 (2d Cir. 1925).

12 This is a very general description of conspiracy doctrine. Conspiracy law may vary from state to state. It is beyond the scope of this report to cover the complexity of this doctrine. See NYPL Art. 105 for New York conspiracy law and 18 U.S.C. § 1962(d) for RICO Conspiracy.

13 Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60, 80 (1942). 14 Id.

15 For an explanation of the relative merits of conspiracy versus RICO charges by a former United States Attorney, see Dwight Holton, Trump Investigations and the RICO vs Conspiracy Puzzle, Just Security, Mar. 14, 2019. Available at https://perma.cc/62NQ-8ZLX.

16 The Double Jeopardy Clause of the 5th Amendment provides that “no person shall be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life of limb” and protects against a second prosecution for the same conduct after either acquittal or conviction and multiple punishment for the same offense.

17 While there is no statute of limitations on murder, the statute of limitations for most felonies in New York is 5 years, and for misdemeanors (such as marijuana sale) 2 years.

18 Krulewitch v. United States, 336 U.S. 440, 453 – 454 (1949)(Jackson, J. concurring).

19 Id. at 445-46.

20 Despite the purpose of RICO, case law has permitted the “interstate commerce” element to be satisfied by minimal impact.

21 Although this report is based on public records, the authors have opted to refer to defendants by their initials to preserve their privacy as much as possible.

22 Preet Bharara Press Conference USAOSDNY, 120 Members Of Street Gangs In The Bronx Charged In Manhattan Federal Court, YOUTUBE (Apr. 27, 2016), https://perma.cc/7LNR-9PJC.

23 RICO Act supra n. 1

24 For information about eligibility for representation by the Criminal Justice Act Panel, see Revised Plan for Furnishing Representation Pursuant to the Criminal Justice Act, 5 (2017) available at http://www.nysd.uscourts.gov/file/forms/current-criminal-justice-act-plan.

25 A review of the judgments of conviction show imposition of minimum fines (either $100 or $200) on every defendant and no other fines.

26 For historical data on stop-and-frisk, see Stop-and-Frisk in the de Blasio Era, New York Civil Liberties Union, 6 (Mar. 2019); available at https://www.nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data.

27 Broken Windows policing refers to aggressive policing focused on low level misconduct and offenses to public order.

28 New York Criminal Procedure Law, Art. 720.

29 New York Criminal Procedure Law, Art. 722.

30 A request for race demographics was denied. FOIA request dated 10/2/18, tracking number EOUSA-2019-000093.

31 The SDNY released a statement providing the age of every defendant in years on April 27, 2016 when it unsealed the indictment and made related media statements. See Press Release, Preet Bharara, United States Attorney Southern District of New York, (April 27, 2016),https://perma.cc/SLV7-F4WF.

32 Press Conference supra at n. 21.

33 Indictments available at bronx120.report.

34 Prosecutors with the SDNY asked for suspension of speedy trial requirements for the 120, and demanded secrecy for all discovery materials, denying the public the right to understand the proceedings and defense counsel adequate opportunity to prepare.

35 18 U.S.C. 1962(d).

36 21 U.S.C. 846; 21 U.S.C. 860.

37 18 U.S.C. 924(c).

38 Parrish indictment, paragraph 19, pp. 23-24. Burrell, paragraph 18, pp. 24-25. For those who displayed or discharged a weapon the plea allocution and disposition sentence reflected these facts, but the initial indictment did not distinguish between those who “used” firearms in furtherance of the conspiracy by possessing them and those who displayed or discharged firearms.

39 The “other” disposition charges include two misdemeanor charges, an assault on a federal officer, and several slightly different charges levied against the two defendants who went to trial. The “other” charges were added by superseding indictments or informations.

40 To prove a RICO criminal enterprise, a pattern of racketeering activity involving two or more predicate offenses or acts is required. The list of predicate offenses includes both state and federal crimes. See RICO: An Abridged Sketch, supra n. 1.

41 The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment has been interpreted not to bar repeat prosecution in a different jurisdiction (the “dual sovereignty test”) or where new charges contain different elements than prior convictions (the Blockburger test”). See, United States v. Lane, 260 U.S. 377, 385 (1922)(dual sovereignty test); Blockburger v. United States, 284 U.S. 299 (1932)(elements test).

42 A white paper by a federal prosecutor helps to explain how and why the prosecutor would even access non-criminal contacts. When targeting a crew, that paper directs prosecutors to pull all police incidents relating to targets “whether they are suspects, witnesses, or victims. No exception. . . . Convictions, acquittals, dismissals, no charges – they all should be pulled.” K. Tate Chambers, Developing a Step-by-Step Application of the New Orleans Strategy to Combat Violent Street Crews in a Focused Deterrence Strategy, Central District of Illinois.

43 New York Criminal Procedure Law §720.35.

44 Kevin Sack, Door-Busting Drug Raids Leave a Trail of Blood, New York Times, Mar. 18, 2017; and Kevin Sack, Murder or Self-Defense if Officer is Killed in Raid, New York Times, Mar. 18, 2017.

45 Mihir Zaveri, Houston to End Use of ‘No-Knock’ Warrants After Deadly Drug Raid, New York Times, Feb. 19, 2019.

46 Ashley Southall and Nate Schweber, Man Wanted for Robbery Plunges to Death During Gang Roundup, New York Times, Apr. 27, 2016.

47 Charles Doyle, Bail: An Overview of Federal Criminal Law, CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE, July 31, 2017. Available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40221.pdf.

48 The Bail Reform Act of 1984, 18 U.S.C. §§ 3141-3156.

49 18 U.S.C. §3142(e)(3)(A),(B).

50 Doyle supra n. 47 at 24.

51 Transcript of May 2, 2016 conference in United States v. Burrell, 10:00, p. 9, lines 19-21.

52 Order dated May 2, 2016.

53 Order dated January 30, 2017.

54 Transcript supra n. 50 at p. 28, lines 19-21.

55 For information on the Rampart Scandal, see, Erwin Chemerinsky, An Independent Analysis of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Board of Inquiry Report on the Rampart Scandal, 34 Loyola of L.A. L. Rev. 545 (2001), available at https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?httpsredir=1&article=2262&context=llr; and Joe Domanick, Blue: The LAPD and the Battle to Redeem American Policing (2015).

56 Ali Winston, Looking for Details on Rogue N.Y. Police Officers? This Database Might Help, New York Times (Mar. 6, 2019).

Acknowledgments

This report was written and researched with support from Vital Projects at Proteus. The authors thank Annemarie Caruso, Fred Magovern, Julia Perez Rosales, Jenny Roberts, and Naree Sinthusek for their feedback on drafts of this report. We thank the attorneys who took the time to answer questions relating to the federal process. The authors would also like to thank family and community members affected by various mass indictments for inspiring this work and Alex Vitale for proposing the project. Fred Magovern provided critical technical assistance to organize data for this report and for the website. Special thanks to Paul Gagner for his patient and meticulous design work. Any errors in the reproduction or interpretation of the data are the responsibility of the authors.